- Home

- Soos, Troy

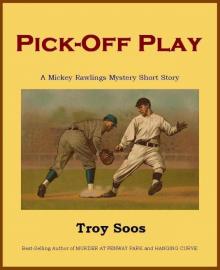

Pick-Off Play (Mickey Rawlings Baseball Mystery)

Pick-Off Play (Mickey Rawlings Baseball Mystery) Read online

Reviews of Troy Soos’s Mystery Novels

“Full of life.”

– New York Times

“Baseball and mystery team up for a winner.”

– USA Today

“A richly atmospheric journey through time.”

– Booklist

“Rawlings turns double plays and solves murders with equal grace.”

– Publishers Weekly

“Troy Soos does a red-letter job of mixing the mystery into a period when all baseball was played on fields that had real grass.”

– St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“An entertaining double play. . . The plot will appeal to mystery fans, baseball purists will appreciate Soos’s attention to detail.”

– Orlando Sentinel

“A perfect marriage between baseball and mystery fiction.”

– Mystery Readers Journal

“You don’t have to be a baseball fan to love this marvelous historical series.”

– Meritorious Mysteries

“Equal parts baseball and mystery are the perfect proportion.”

– Robert B. Parker

“Authentic old time baseball atmosphere and absorbing stories. Troy Soos captures the period perfectly.”

– Lawrence Ritter, author of The Glory of Their Times

Also by Troy Soos

Mickey Rawlings Historical Baseball Mysteries:

Murder at Fenway Park

Murder at Ebbets Field

Murder at Wrigley Field

Hunting a Detroit Tiger

The Cincinnati Red Stalkings

Hanging Curve

Marshall Webb – Rebecca Davies Historical Mysteries:

Island of Tears

The Gilded Cage

Burning Bridges

Streets of Fire

Nonfiction Baseball History:

Before the Curse: The Glory Days of New England Baseball

Mystery Short Stories:

Decision of the Umpire

Pick-Off Play (Mickey Rawlings)

Pick-Off Play was originally published in the baseball mystery anthology Murderers’ Row, New Millenium Press, 2001

Kindle Edition of Pick-Off Play copyright 2012 by Troy Soos

Pick-Off Play

From where I sat—kneeled, actually, in the on-deck circle near the Beaumont Oilers’ dugout—it looked like Archie Hines was out by a mile. The five or six hundred fans scattered about Magnolia Ball Park’s weather-beaten grandstand probably saw the play the same way. If so, we were all wrong. The plate umpire’s arm was extended toward first base, awarding Hines the bag. The only thing that prevented him from taking it was the fact that he was dead.

I’d been coached since childhood to keep my eyes on the ball, and that’s exactly what I had done, watching the Houston Buffaloes’ third baseman as he scooped up the two-hopper and threw to first. I hadn’t noticed that Hines had never left the batter’s box where he now lay motionless.

As soon as I spotted Hines on the ground, I dropped my bat and ran to him. The potbellied old umpire and the Buffaloes’ catcher, masks in hands, were standing helplessly over the young shortstop. Murmurs rippled through the stands as the fans began to realize that something was terribly wrong. My fellow Oilers and several of the visiting Buffaloes soon joined the circle around the fallen ballplayer. All stood immobile, at a loss for a way to aid him.

The umpire finally grunted, “He ain’t movin’.” It was one of the few calls he’d gotten right all day. He spat a shot of tobacco juice toward the backstop. Some dripped onto his ill-fitting blue serge suit as he bellowed to the crowd, “There a doctor here?”

I stared down at Archie Hines, my teammate and roommate. The wiry nineteen-year-old, just off a 1912 season in which he’d led the Texas League in stolen bases, was known for his speed. It seemed he was always in motion, dashing around the base paths or ranging for grounders at short. Now he lay like a pile of dumped laundry, not the slightest twitch from his limbs. Nor from his open glassy eyes. The only thing moving on his body was the blood that trickled from his crushed left temple and seeped into the clay around home plate.

His very life seemed to be evaporating in the July sun, shimmering off on ripples of steamy air. As I looked at Hines, at his broken skull and his blond hair now stained red, I could almost hear the echo of the ball that struck him and in my mind’s eye I replayed his last at bat.

Hines had led off for us in the bottom of the fourth inning. With a one-strike count on him, Jake Pruett’s next pitch came at his head. Hines ducked, and it appeared that he’d evaded the ball—the sharp crack that split the air sounded as if his bat had taken the impact. The ball quickly bounded up the base line, where the Buffaloes’ third baseman fielded it. What had confused everyone, I realized, was the terrific distance the ball had traveled. Once more the crack reverberated in my ears, and I could detect the subtle difference in sound of horsehide on bone instead of on wood.

A gangling young man in a straw boater and a seersucker suit hopped the railing and approached the ump. “Perhaps I can help.” He had no black bag with him, but I could tell it didn’t matter—nothing in any black bag could help Archie Hines now.

“You a doctor?” demanded the ump.

“No, but my father is.”

“My mother was a seamstress,” said the ump. “Don’t mean I can sew a stitch.” Then he shrugged. “Go ’head. Take a look at ’im.”

The young man began to kneel, then decided against messing his trousers in the bloody earth. He squatted instead, and took Hines’ wrist in his hand, feeling for a pulse. The sad shake of his head indicated that he detected none. Next he looked into Hines’ ghostly eyes while muttering softly to himself. When he picked up the shortstop’s cap and placed it gently over his face, the action informed everyone in the ballpark that Archie Hines was dead.

While gasps of disbelief whooshed about the stands, the Houston Buffaloes’ first baseman realized that he’d been holding the ball that had killed Hines. He placed it on home plate as if it had suddenly become hot to the touch.

I backed away from the others and turned toward the mound. Hulking Jake Pruett, who’d delivered the fatal pitch, stood lazily with his hands on his hips. A smirk creased his unshaven face, and his pale eyes sparkled with amusement.

“You think this is funny?” I yelled at him.

Pruett tilted back his cap at an arrogant angle and the smirk broadened to a grin.

“You sonofabitch!” I took off for the mound, determined to alter his expression.

A couple of strides from my target I was tackled from behind and wrestled to the ground. A number of hands were soon pinning me down. While I struggled to break free and get at Pruett, I noticed that the uniforms of my captors were all home whites—it was my own teammates who were holding me in place.

One of them was our catcher, Stump Williams. “It happens, Mickey,” he wheezed, while trying to grab my flailing right arm. “Leave it be.”

“Bastard is smiling! He killed Archie and he’s happy about it.”

“C’mon, Mick,” Williams said. “It was an accident. Can’t blame Pruett.”

I twisted my head to look at the pitcher. If it was an accident, he showed no signs of regretting the result. Seeing me secure in the clutches of my teammates, he raised a finger to the bill of his cap and touched it like a salute. A salute of triumph.

I renewed my struggles to get at the gloating pitcher, while two more Oilers joined the others trying to hold me down.

“Rawlings!” George Leidy barked at me. “Get your ass over here!”

I finally calmed down enough to obey the man

ager’s order. With teammates close on either side of me to make sure I didn’t go after Pruett again, I returned to home plate.

Leidy said to me, “Don’t go making things worse than they are already.” Then he shot Pruett a look that indicated he wouldn’t mind getting in a couple of punches at the pitcher himself.

Players of both teams began to mill about home plate restlessly. One of the Buffaloes looked down at Hines and said, “Gonna hafta move him if we’re gonna finish the game.” I wondered how he could even think of continuing, then realized it could matter to Houston’s pennant hopes. They were ahead 5-1 in the fourth inning; if the game was called off, it would have to be played over completely and they’d lose that lead.

The umpire finally conferred with the two managers. He began by pointing out that Hines was entitled to first base but would need a pinch runner if we played on. I glanced at my teammates; not one appeared willing to pinch run for a dead man.

Despite a token protest from the Houston manager, the plate ump eventually decided to call off the game. I’d been in lots of games that ended early because of darkness or rain, and once in North Carolina because of a swarm of bees. This was the first time I’d been in a ballgame that was called on account of death.

* * *

Since Magnolia Ball Park had no changing facilities, I walked the three blocks home in full uniform having only swapped my spiked shoes for bluchers. As always, I carried my gear—three homemade bats and a Spalding mitt—in a canvas bag slung over my shoulder. What was different was that Archie Hines usually made the walk with me. Today I carried the glove that he would never use again.

Like many of the Oilers, Archie and I lived at Mrs. Kitzler’s boarding house on

Hazel Street. I had no intention of finding more permanent housing in Beaumont. To me, the Gulf town was nothing more than a brief detour on my way back to the major leagues. I had spent most of last season as a utility infielder with the World Champion Boston Red Sox, and ached for another shot at the majors. I even paid my rent by the week instead of by the month because I kept hoping that I would soon be called to play the rest of 1913 with a big league club. Back in our room, which Mrs. Kitzler furnished in a style that would be considered stark by most prison standards, I sat on my lumpy iron-rail bed and stared down at Archie’s old mitt. I noticed that the palm of the black leather glove was worn clear through, and the seam where the thumb was attached had been crudely restitched at least twice with different colored threads.

Archie Hines was the most frugal young ballplayer I’d ever met. He told me that he grew up in a Pennsylvania coal town, living in a company shanty. Until two years ago, the most money he’d ever made was $1.50 a day for mining anthracite plus a dollar on Sundays for playing semi-pro ball. Now he was earning an almost princely salary—eighty-five dollars a month, the same as me—but he still refused to pay two bits for a new shirt collar. Instead, he rubbed clean his old celluloid collar until it was almost transparent. His one suit, hanging among the row of pegs that Mrs. Kitzler called a “closet,” was ten years out of style and shiny at the elbows.

I ran my thumb across the repair stitches on his glove and wished I had thought to buy him a new one. Although I was only two years older than Archie, from the time we started rooming together he had looked up to me. I knew it was largely because I had already achieved his dream of playing big league baseball. He often pressed me to tell him about playing against Ty Cobb and Walter Johnson and Joe Jackson—stories I was always happy to repeat—and he’d tell me eagerly how he couldn’t wait to face them himself. Also, since I had traveled more of the country than he had, Archie thought me “worldly” and asked my advice on everything from how to sleep comfortably in a Pullman car to which fork to use in a restaurant. Sometimes when I didn’t know an answer, I made one up because I hated to be a disappointment to him.

I’d felt responsible for Archie, and somehow it seemed that I had let him down today by failing to protect him. He was a good roommate—didn’t smoke or drink, and most importantly didn’t snore—but more than that Archie Hines was a decent kid, and he didn’t deserve to die so young.

I wasn’t the only one who thought well of Archie. In an oval wooden frame next to the washstand was a photograph of a plain, well-fed girl with a kind face and curly hair. It was Ella, his girl back home and the main reason for Archie’s thriftiness. He was saving up to marry her. Archie planned to make their engagement official the day that he made it onto a major league roster, and with his ability I had no doubt that they would have become engaged soon. Who was going to tell Ella, I wondered, that it was now never going to happen? One pitch, one split second, and lives were changed forever.

I tried to suppress it, but the image of Archie Hines’ final at bat came fresh to mind. Then came the memory of Jake Pruett’s smirking face. I couldn’t reconcile Pruett’s pleased expression with the circumstances of the tragedy. There was no reason for him to bean Hines intentionally—he hadn’t been crowding the plate, nor had he been hitting Pruett well enough for the pitcher to want to shake him up. So the pitch must have simply gotten away from him. But then Pruett should have looked embarrassed at his wildness. Or sorry about the result. Maybe even defiant, as if to say, ‘Don’t blame me, it happens sometimes.’

I’d seen more than a hundred pitchers over the years and studied them closely. What I saw of Pruett today stood out as the most peculiar reaction I’d ever witnessed. I could think of no way that any pitcher would look so satisfied about what had happened to Archie Hines. Perhaps I was missing something, I decided. Perhaps a player who’d faced many more pitchers than I had could explain it to me.

* * *

A single bathroom at the end of a dingy hallway was shared by all of Mrs. Kitzler’s residents. As I entered, I almost laughed at the sight in the ancient zinc bathtub. Only a reclining face was visible above the surface of the water, looking like a craggy, leathery island. Towering from the mouth was a lit black cigar, giving the impression of a lighthouse.

“Stump!” I called, but the sound didn’t reach his submerged ears. I banged on the rim of the tub and he popped his head up, the cigar almost falling from his teeth. With his moon face and flattened nose, Williams’ head resembled a lumpy catcher’s mitt. His body was even less attractive, showing the scars and knocks of twenty years and more than a thousand games.

“You mind if I shave?” I asked. The bathroom was Stump Williams’ exclusive domain after a ballgame. In deference to the veteran’s age, the rest of the team always let him have a long soak alone before taking our own turns.

“Nah, I don’t care,” the old catcher growled.

My scant whiskers could easily wait another week, but it gave me an excuse to be here. “You been in baseball a long time,” I said, stirring my shaving brush in the soap mug.

“Yup. And I’m gonna be in baseball a long time, too.” That was wishful thinking on his part. Stump Williams was sliding back down the ladder of organized baseball; in a couple of years he’d be lucky to be playing semi-pro for a couple bucks a game.

“You see Jake Pruett much?” I asked. Williams and Pruett were both veterans of the game, I knew, and about the same age.

Williams puffed hard on his cigar until the tip burned brightly. “For a few years I did. Back when I was with Pittsburgh and he was pitching for Brooklyn.”

“What do you know about him?”

He gave me a baleful stare. “Look kid, I been around long enough to know how easy it is to get hurt on a ball field. Hell, I been spiked, beaned, and got broken bones from my nose to my toes. It happens. Leave it be.”

I put down the shaving brush, giving up any pretense that I was here for any reason other than to ask him about the man who killed my roommate. “I expect you’re right,” I said. “But I can’t leave it be. Not yet.”

He exhaled a cloud of acrid smoke. “Suit yourself, kid. But I tell you: You’d be better off thinking about tomorrow’s game than today’s. Archie is dead, and he’s

gonna stay dead. Don’t worry about things you can’t change.”

I nodded, but pressed on, “So what do you know about Pruett?”

Williams sighed in surrender. “Can’t say I knew him well. Didn’t run into him off the field much—didn’t particularly want to.”

“Why not?”

“Jake Pruett didn’t only pitch for Brooklyn. He was born and bred there, and wanted everybody to know it. Thought he had the reputation of the city to keep up, so he always tried to act the tough guy. Always had a scheme going, too—cheating at cards, hustling pool, you name it. Oh yeah, and he’d sell ‘gold’ watches that weren’t worth two bits.” Williams shook his head. “Pruett was small-time, though, and harmless enough as long as you kept a firm grip on your wallet.”

“What about on the field? He like to throw at batters?”

“No more’n any other pitcher. The plate was his, and he’d let you know it. Crowd too close, and he’d sit you on your ass. But that’s the way the game is played.”

“How was his control?”

Williams puffed noisily before answering. “Pruett could put the ball wherever he wanted—fastball and curveball both. Never tried a spitter, as far as I know. But even the best pitchers can get wild now and then.” He took the cigar in his fingers, but it slipped and fell into the tub with a sizzle and a splash. “Damn!” He groped frantically in the tub and pulled up a soggy mess of tobacco. “Get me another, would you?” He gestured toward his jacket hanging on the back of the door.

I wiped the lather from my hands and dug into his pocket for a fresh cigar and a match. “Why do you think Pruett was smiling the way he was?”

“Hell, kid, I dunno. I wasn’t really looking at him anyway—I was looking at poor Archie. But you can never tell how somebody’s gonna react to something like that.” He bit the end off his cigar and I gave him a light. Then he submerged himself again, the conversation over.

Pick-Off Play (Mickey Rawlings Baseball Mystery)

Pick-Off Play (Mickey Rawlings Baseball Mystery)